When the outbreak first arrived in Afghanistan, I went to a town on the Afghan border where thousands of Afghan migrants returned from Iran to escape the pandemic.

On one day in March, over 11,000 crossed. As I stood over a sea of young men inside the small immigration center, I wondered: How can I put a human face onto a pandemic in a country already ravaged by war?

Fifteen members of the Sayedkheli family crossed the border. I began to document their journey to their ancestral home in the northern province of Parwan. They had fled Parwan years ago for a better life.

Two brothers who had served in the Afghan military knew their future: Back to their uniforms and guns, back to war. But weeks after their return, they felt heartbroken not by the return to war, but by the stigma they received from the community for leaving Afghanistan.

“It’s a knot in my heart,” said Khaled, almost choking. “People don’t even want to talk to me from a distance because they know I have come from Iran.”

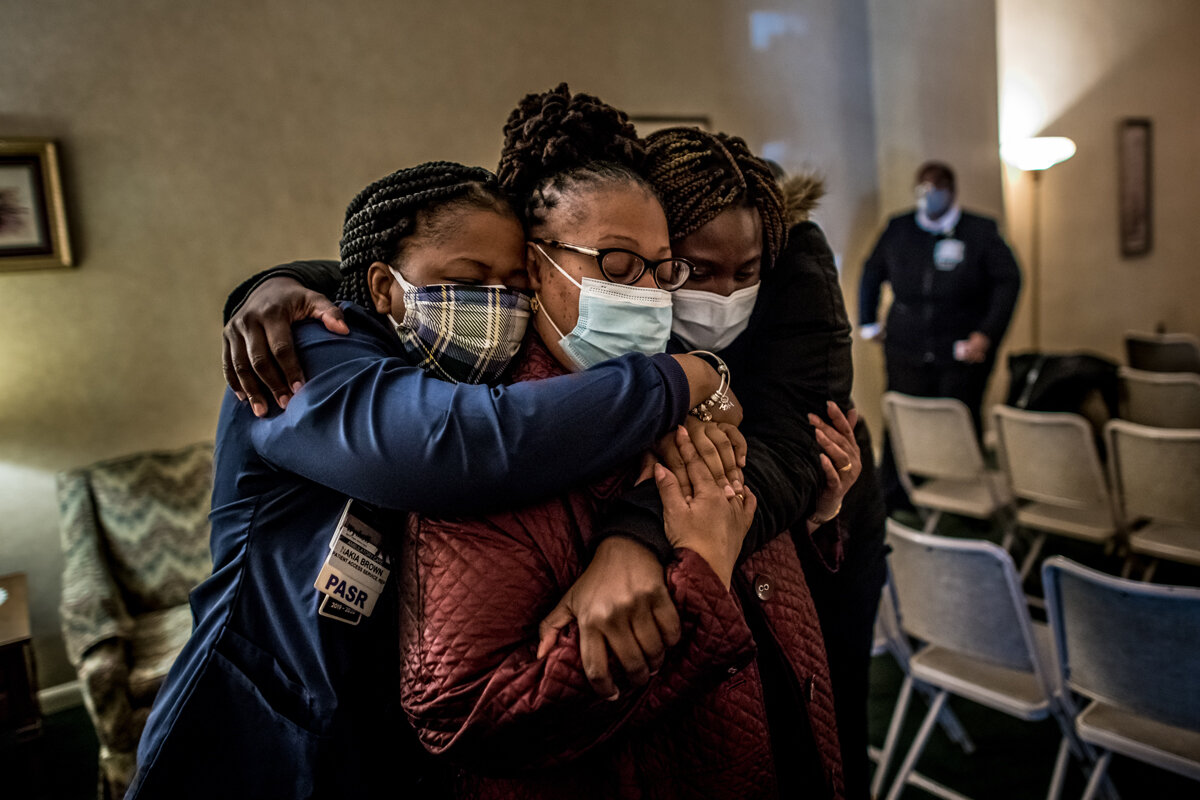

It is a double-edged sword, this pandemic ravaging through our world. On one hand, it pulls us apart with travel bans, social distancing, work-from-home and isolation. We sit six feet apart, pondering how to console a friend without embracing. We’re forced behind windows or mobile phones to watch loved ones take their last breaths. And we wonder if life will ever be the same.

On the other hand, this is the first time in my life that the world is collectively experiencing a crisis. It forces even privileged societies ― those that often observe “the pain of the others” ― to regard their own loss and suffering. To feel pain at its core.

This time is a crucial moment — a moment, that if utilized well, can bring us together. And photojournalists play an essential role in documenting this time with compassion and empathy.